The October 7th Venture Doctrine

New defense VCs, led by former generals, are betting that Oct 7 created the conditions for Israel to become the R&D arm of Western defense technology.

Welcome to Israel Tech Insider, a newsletter making sense of Israeli tech. It’s written by me, Amir Mizroch, and made possible by paid subscribers. Please consider becoming one of them.

As always, feedback to amir@israeltechinsider.com

Agenda:

Major General Venture Partners: The October 7th Venture Capital Doctrine

Buyout firm Thoma Bravo in talks to buy Israel’s Verint

The Israelis building AI products for Big Tech

Investment rounds

Major General Venture Partners

TL:DR: Israeli defense VC is loading up on army vets who understand system failures to create venture-backed solutions. But major challenges loom.

Apart from political paralysis, intelligence groupthink, and unmitigated hubris in disrespecting the enemy, October 7th revealed a specific technological gap: the inability to rapidly integrate commercial technologies into battlefield systems. Now, new Israeli defense funds are betting this gap creates an investable category.

CHAMPEL Capital's $100 million and Kinetica's $150 million represent $250 million in new Israeli defense venture capital. The tell is in the talent, not just the capital allocation.

Retired General Giora Eiland's CHAMPEL Capital is the biggest example yet. Eiland spent 33 years in the IDF, including head of Operations during the Lebanon withdrawal and National Security Council chief during Gaza disengagement. His post-retirement trajectory—18 years building defense consultancy relationships—will be helpful in both the institutional failures and the venture capital solutions.The advisory roster crystallizes the strategy: former Rafael CEO Yoav Har-Even for defense industry access, ex-police chief Kobi Shabtai for domestic credibility, and US urban warfare expert John Spencer for Pentagon legitimacy.

Kinetica's founding partners include Maj. Gen. (res.) Saar Tzur, former commander of the IDF Northern Formation, and Brig. Gen. (res.) Amit Kunik, a former senior intelligence official. The advisory board adds former U.S. Navy Secretary Kenneth Braithwaite and former Senator Norm Coleman.

Earlier this year, Major General Amikam Norkin, former commander of the Israeli Air Force, founded Ace Capital Partners, an aerospace and defense tech VC.

But do ex generals make good investors? And what specific challenges will these former soldiers be best place to overcome?

A good place to start is the undeniable fact that defense tech requires longer development cycles than typical venture capital timelines, while complex procurement processes create extended sales cycles that can kill tech startups.

The regulatory burden alone is formidable. Israeli companies must navigate dual oversight—the Ministry of Economy for civilian dual-use technologies and the Defense Export Control Agency for military exports—while simultaneously complying with U.S. export controls. Companies using American components face strict International Traffic in Arms Regulations, creating overlapping compliance burdens that significantly increase operational costs.

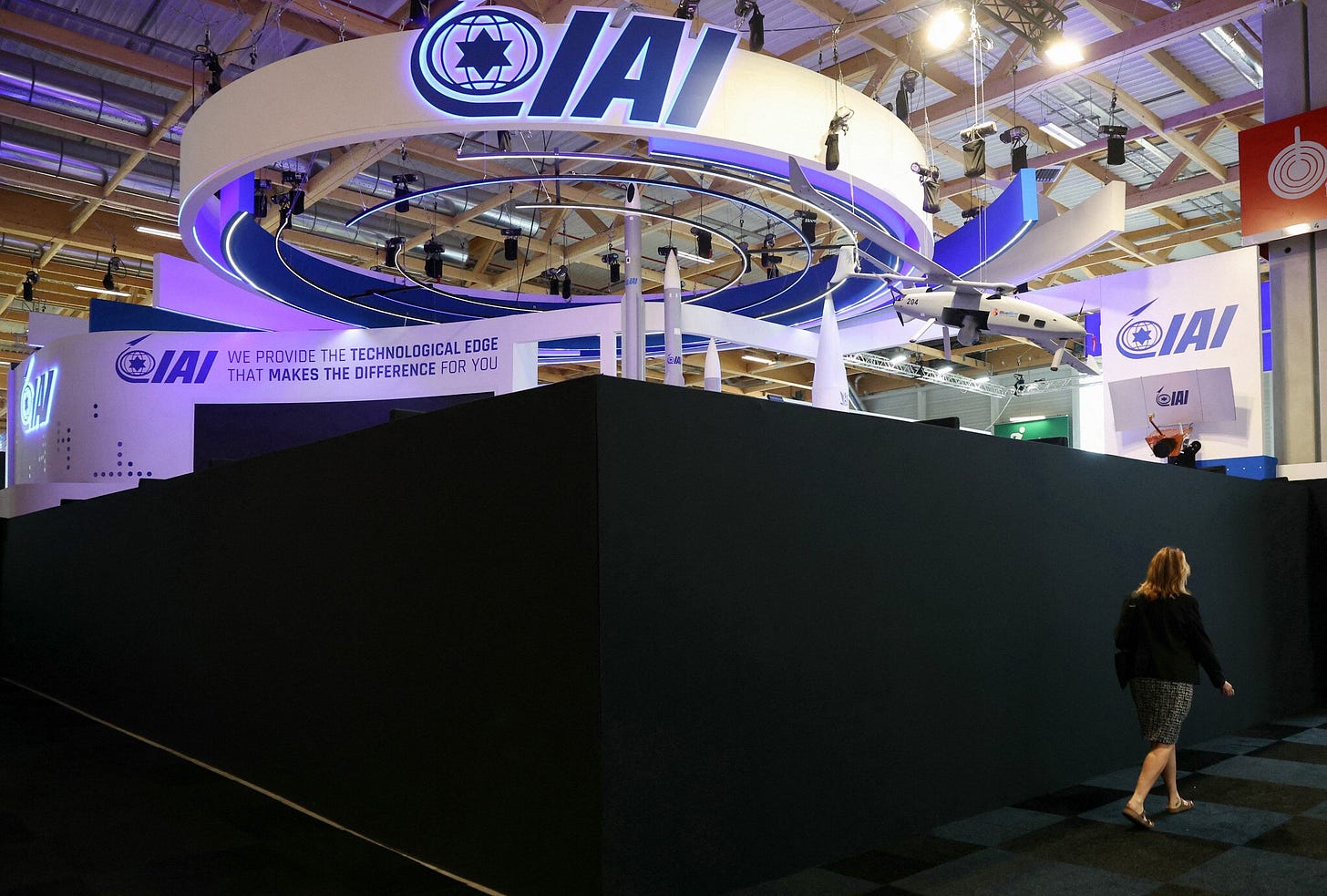

The Europeans aren’t that much better. Actually they’re worse. France banned Israeli defense companies from major exhibitions, requiring weapons systems to be concealed behind black barriers at the Paris Air Show.

Britain suspended 16 of 368 Israeli defense licenses, while 17 EU countries initiated reviews of Israel's compliance with human rights provisions. Even where formal restrictions don't apply, "silent resistance" from European partners creates operational delays and compliance costs, forcing companies to dedicate substantial resources to relationship management rather than innovation.

The talent crunch poses perhaps the greatest long-term threat. Israeli defense tech's heavy reliance on military veterans creates acute vulnerabilities during extended conflicts. Many companies report 50% workforce deployment to reserves, requiring complex contingency planning to maintain operations. This challenge is compounded by broader emigration patterns—8,300 high-tech workers left Israel between October 2023 and July 2024, representing the first workforce decline in a decade. The sector that built its advantage on elite military talent now struggles to retain it during the very conflicts that validate its technologies.

But help is on the way

Palantir co-founder Joe Lonsdale's advisory role with Kinetica transfers Palantir's "Forward Deployed Engineers" model to Israeli defense tech, where engineers work directly alongside military customers at battlefield speed. The funds are betting that October 7th created the conditions for Israel to become the R&D arm of Western defense technology. Lonsdale has been systematically building what he calls the "Rebel Alliance" of defense startups since 2015, with early investments in Anduril.

Kela Technologies, which raised $100 million in its first year from Sequoia, Lux Capital, and the CIA’s In-Q-Tel, was co-founded by Hamutal Meridor—the former General Manager of Palantir's Israeli operations and former Unit 8200 alumni. Sequoia's investment rationale for Kela explicitly states the goal of leveraging Israel's "unique cadre of 'techno-warriors' to help defend the Western world order," with plans to position Israel as "a strategic asset for NATO and the United States."

Kela’s product enables militaries to integrate commercial AI, sensors, and edge devices into military systems in real-time. Apart from Meridor, Kela's founding team combines Talpiot program graduates (Alon Dror, who won the Israel Defense Prize), and weapons development engineers from the Intelligence Corps' elite technology unit (Jason Manne). This represents institutional memory about what specific technologies failed on October 7th and why.

Line 5's $20 million seed round—the largest global defense tech seed in 2025—was founded by Gigi Levy-Weiss and Yiftach Shoolman. Levy-Weiss, a former Israel Air Force combat pilot turned venture capitalist (NFX ventures), partnered with Shoolman, co-founder of Redis and former Sayeret Matkal operator. Sayeret Matkal (General Staff Reconnaissance Unit) is the IDF's premier Special Forces unit, comparable to Delta Force. The company's CTO, Matan Melamed, co-founded Iron Drone, one of the IDF's key counter-drone technologies.

These aren't just more startups or VCs trying to break into the defense establishment—they're defense establishment veterans using startup methodologies to solve problems the traditional system can't address. Lonsdale's November 2023 essay “Our Duties as Defense Technologists” frames this challenge explicitly: "Evil exists in the world. The United States sometimes has to fight against it. Technological superiority is absolutely essential to our defense, which obligates technologists to participate." Israel is no different.

Splitting headcount from productivity: Israeli tech’s future?

Israel's high-tech sector is performing economic acrobatics that would make central bankers reach for their leotards. In the first quarter of 2025, the sector generated 11.8% output growth while employment crawled forward at just 1.4%—a productivity surge of nearly 10% annually that economists are still trying to find historical precedent for. Is this something temporary of a fundamental shift? 395,000 workers now comprise only 11.3% of Israel's workforce (down from 12.5% a year earlier) yet drive 56% of national exports, creating dangerous economic concentration around cyber, defense, and AI technologies.

R&D positions fell 2.1% while business roles jumped 7%, suggesting more focus on commercialization. The productivity explosion stems from brutal efficiency gains—fewer junior hires, reduced recruitment overhead, AI integration in development, and potential brain drain as talent emigrates while remaining workers shoulder expanded responsibilities. Defense industries' contribution to high-tech exports has reached 56%, reflecting wartime demand but raising questions about economic diversification.

Is this what resilience looks like? A capital-intensive, employment-light engine that strengthens Israel's economic position while potentially exacerbating inequality. What happens if peace suddenly breaks out? Too horrible to imagine.

Thoma Bravo Verint Over

[[Disclosure: Back in 2020 I advised Verint on its split of its cyber and surveillance operations business as a separate company called Cognyte]].

Private equity heavyweight Thoma Bravo is reportedly in talks to acquire Verint Systems, a veteran of Israel’s tech scene best known for its call center software—think chatbots, automated call routing, and speech analytics. Verint’s been stuck in slow-growth mode for over a decade. Its stock has dropped 43% in the past year. That’s during a time when the Nasdaq tech index nearly doubled.

Investors were quick to respond to the deal chatter: Verint’s shares jumped 16% after-hours on July 1. The company is now valued at just over $1.1 billion, despite bringing in nearly $1 billion in annual revenue. That mismatch—low market value compared to its sales—makes it a textbook target for private equity firms like Thoma Bravo, which specialize in buying underperforming companies, restructuring them, and selling at a profit.

What’s Gone Wrong?

Verint has struggled to modernize. It was slow to adopt a subscription-based pricing model—now standard in the software world—where customers pay monthly or annually instead of making one-time purchases. Its Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR), a key metric in SaaS businesses, is growing faster than overall revenue (around 8%), but that’s not saying much when topline growth is stuck around 3%.

Profitability is slipping too. Verint’s gross margin—the amount left over after direct costs—is down to 69.9% from 72.4% last year. Its adjusted net income fell 57%, to just $18.5 million. Meanwhile, many of its AI-powered tools are only available to cloud customers, limiting their adoption.

Verint’s “neutral platform” strategy—staying independent of phone or cloud providers—once made sense. But rivals like NICE, another Israeli firm, have since built end-to-end systems that bundle telephony, cloud, and AI in a single package. That’s easier for buyers—and harder for Verint to compete with.

Why Thoma Bravo Might Want It Anyway

Dig a little deeper, and Verint’s value proposition gets more interesting. The company doesn’t just manage customer service interactions—it analyzes them in real time, looking for patterns, detecting fraud, and predicting customer behavior using machine learning. That’s especially appealing to large enterprises, banks, and telecoms, where customer experience and security increasingly overlap.

Thoma Bravo has experience here. It previously acquired Israeli-founded cybersecurity firm Imperva for $2.1 billion in 2019, then sold it for $3.6 billion in 2023. It also owns other big names in cyber and enterprise tech, including Sophos, Proofpoint, and Darktrace.

For Thoma Bravo, Verint could be more than just a turnaround project. It could become part of a larger strategy: integrating customer engagement and security into a single, AI-driven enterprise platform.

The Israelis building AI for Big Tech

Eti Fakiri joins Meta’s new Superintelligence Lab and will be moving to Silicon Valley. Meta chif Mark Zuckerberg established the lab in response to competitive pressure from rivals like Google, OpenAI, and DeepSeek following poor reception of Meta's Llama 4 model and senior staff departures. The strategic pivot involves aggressive talent acquisition through million-dollar packages targeting researchers from OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google, alongside a $14.3 billion investment in Scale AI, as Meta seeks to accelerate artificial general intelligence development and create new revenue streams from AI applications.

Elan Dekel is building AI products Amazon’s AGI Lab in SF and he’s hiring.

Moshe Patel, Director of the Israel Missile Defense Organization (part of the Israeli Ministry of Defense) reveals that the Israeli defense establishment is manufacturing full-cycle anti-rocket interceptors in the US, not just their separate components as in the past. This in response to reports that Israel was running low on interceptors during the 12 day war with Iran. Data shows that Israel’s multi-layered air defense maintained a success rate of approximately 86 percent against ballistic missiles launched from Iran, consistent with previous operations. That figure was bolstered by the rapid deployment of upgraded Arrow missile systems just a week before the conflict began.

Follow the Money

Larry Ellison leads $23M Series B in Imagene AI to build ‘OpenAI for precision medicine’—CTech

IBM-backed Qedma raises $26M Series A to fight quantum computing errors—CTech

What I’m reading

How Israel strangled Iran's terror financing network—Globes

Only US has more big drone companies than Israel—Globes

Jon Medved, View / How Saudi Arabia can follow Israel’s AI blueprint—Semafor